Videogames ate our quarters, won our hearts, and rewired our minds.

—— J.C. Herz

—— J.C. Herz

Let’s go back to the 1950s – 1960s. At that time, computers were huge in shape and expensive in price, equipment only accessible to universities or research institutes. In 1952, Sandy Douglas who was then a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Cambridge developed one of the first games in electronic game history – the tic-tac-toe game “OXO” – with an EDSAC computer. After that, different tabletop chess games were developed into computer versions, allowing modern military wargaming to enter into computing. In 1962, in order to let various users use the computing resources of the massive computer at the same time, the so-called “time-sharing system” was developed; also, another game “Spacewar!” was able to be operated on MIT’s PDP-1 (Programmed Data Processor-1). The time-sharing technology has permitted two players to be connected and fight against each other. This led to the concept of the “personal user”, allowing people to seemingly own a computer of their own.

電腦遊戲吃掉我們的硬幣,擄獲我們的心,並將我們的大腦重新裝配。—— J.C. Herz

首先回到 1950-60 年代。當時電腦體積巨大、造價昂貴,通常只有大學或研究機構才有的配備。1952 年,當時是劍橋大學博士候選人 Sandy Douglas 在 EDSAC 電腦上開發出電子遊戲史上最早的遊戲之一「OXO」井字棋,在此之後,各種桌上棋弈陸續開發出電腦版本,讓現代戰爭兵棋推演進入到電腦計算之列;1962 年,為了讓多位使用者同時使用巨大電腦的運算資源,所謂的「分時系統(time-sharing system)」被開發出來,這時另一款遊戲《太空戰爭》(Spacewar!)便能在麻省理工學院的 PDP-1(Programmed Data Processor-1)電腦上運行,分時技術讓兩位玩家可以連線對戰,「個人使用者」的概念應運而生,讓人彷彿擁有一台屬於自己的個人電腦。

Insert Coins: Stark Peng’s Game Arcade Collection

Games are often used as a display method of computer technology development, helping people to better comprehend some new technologies or functions. In terms of human-machine interface development and computer hardware popularization, games have played an important role. Not only did they rewire our brains but also reshape our outer forms by growing calluses on them. The very famous examples would be Microsoft’s Mines, Solitaire, and Hearts. In the 1990s, these games were built in the Windows systems by Microsoft, allowing users to be more familiarized with the mouse operation. Afterward, the concept of “gamification” together with the digital interface has been vastly applied in different fields, including education, marketing, business management, crowd outsourcing, health management, and other blockchain games featuring the play-to-earn mechanism.

Media theorist Claus Pias mentioned that “the world of the (digital) computer world is itself already a game world” in the book “Computer Game Worlds”. Computers’ operations are based on a set of symbols and clear starting points, just like games. The artistic works created based on computer games have also inherited this essence. The works are sets of procedures, rules, and coding. People can only see its appearance once it is played or executed, or else, it remains in a non-materiality state for most of the time.

遊戲經常作為電腦技術發展的演示方式,幫助人們更好地理解某些新技術或功能。人機互動介面的發展與電腦硬體的普及上,遊戲也扮演重要角色,它不僅將我們的大腦重新裝配,也讓我們長出新的繭。其中一個為人熟知的例子是微軟電腦的小遊戲踩地雷、接龍與傷心小棧,1990 年代被微軟內建在 Windows 系統中,讓使用者熟悉滑鼠的操作。而後遊戲化(gamification)的概念搭配數位介面,更加廣泛地應用在不同領域,包括教育、行銷、企業管理、群眾外包、健康管理,還有許多區塊鏈遊戲主打的邊玩邊賺(play to earn)機制。

媒體理論家 Claus Pias 透過《電腦遊戲世界》一書中提出「電腦(數位化)世界本身已是一個遊戲世界」,電腦依據一套有限的符號與明確的起始點運行如同遊戲一般。基於電腦遊戲所創作的藝術作品也承襲了這樣的本質,作品是一套程序、規則、編碼,唯有當被遊玩或執行時,人們才得以看見其樣貌,其餘時候多半是沒有物質性的狀態。

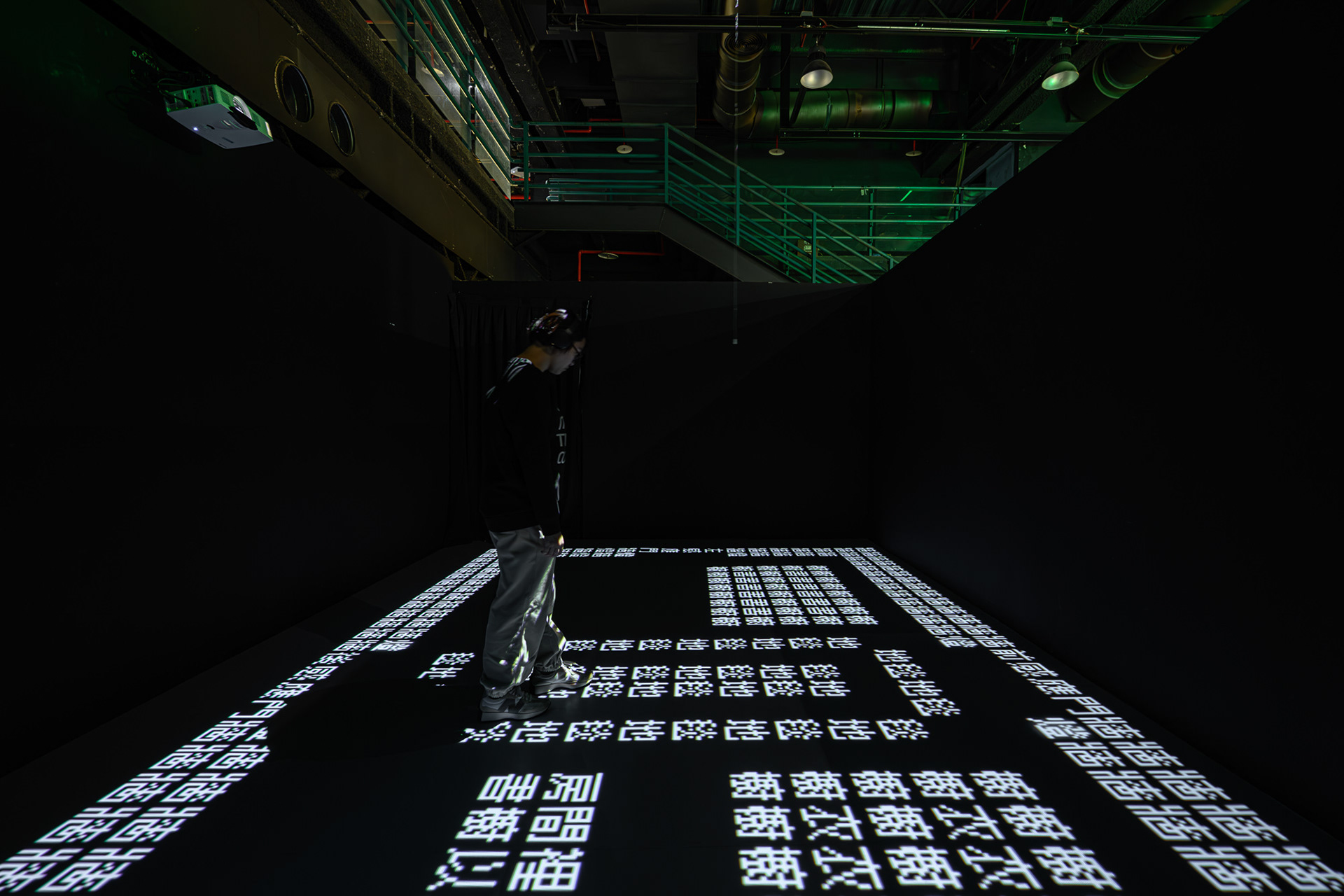

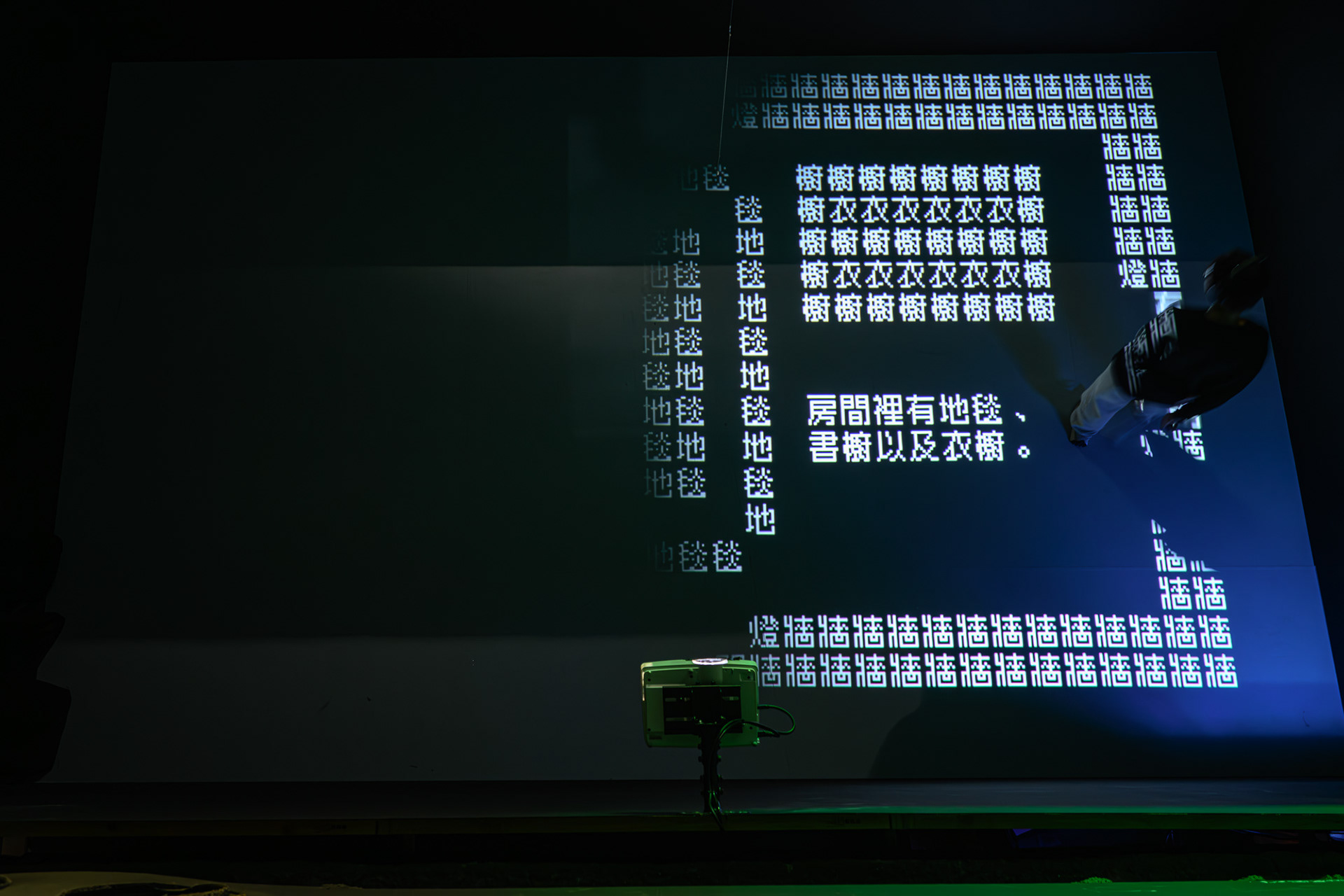

Team9 & David Yang, Make room for words. (2023)

To have an acumen over the intersection of video games and contemporary art from the overview of technological development, we would turn to game engines as integrated development environment that appeared in the 1980s. Game designers were able to get rid of the design development with pen and paper. Then, in the 1990s, when game engines had become the development mainstream, works using engines gradually appeared in the creations of contemporary art. Some of these pieces inherited the DIY culture, hacker culture, and free/open-source software movements of the last two decades, somewhere between 1980 – 1990, as their nutrients. Certain paradigms could be outlined among these creations – the glitch as the aesthetic setting, hacking into the game system, modding, or using games as the narrative method.

若從技術發展概要爬梳電子遊戲與當代藝術的交匯,我們會發現 1980 年代出現作為整合開發環境(Integrated Development Environment)的遊戲引擎,讓遊戲設計師們擺脫以紙筆做設計的開發方式,接著 1990 年代當遊戲引擎成為開發主流,當代藝術創作中也逐漸出現使用引擎製作的作品。這些作品中有許多繼承了 1980-1990 年代這 20 年間 DIY 文化、黑客文化與自由軟體運動的養分,而這些創作似乎可以歸納出幾個典型——將小故障(glitch)當作美學設定、駭入遊戲系統、魔改(modding)或是以遊戲作為敘事手法等。

Nao Usami, Ambiguous Lucy (2021)

Nao Usami, Replay over and over (2023)

Thus, nowadays when more creators are using the game engines, what else may emerge? In “Game Works: On the Aesthetics of Games and Arts”, the designer/curator John Sharp has divided the relationship between games and arts from a massive amount of examples into four categories: Game Art, Artgames, Artist’s Games, and Games as a Medium. Could the framework still be used in the comprehension of current creations? Or else, have the boundaries become more blurry?

On one hand, the exhibition theme “A-Real Engine” alludes to video games as an engine full of energy that keeps driving the development of digital culture. In the common formats of contemporary arts, such as kinetic installations, network art, technology art, encrypted art, and other creations in different aspects, such corresponding technological driving force can always be identified. Certainly, computer games are also included; they can even be evolved into creations like machinima. Computer-game-related software and hardware technologies, design mindset, and contents generated by users have all injected a stream of freshwater into artistic creations. On the other hand, the privative prefix, “A-” of “A-Real” refers to an explicit rejection of the distinctions between real/unreal, online/offline, and virtual/real. It is most probable that such a distinction may be invalid and has never been applied. In fact, games are a kind of reality.

Game engines are the environments and rulesets of game development and operations, whereas exhibitions are the environments in which artworks are being experienced or even completed. Artists build a brand-new narrative through computer game concepts and elements or deconstruct the game mechanism by disassembling the engine. Under guidance, the audience can further understand their own standpoints, or even find a path to escape from the system’s control, becoming a potential rule breaker. Additionally, repairing game consoles that preserve and recreate games that once brought pure joy to people is also an approach, and is one that makes people willing to spend all the coins in their pockets — all of these aspects are presented in the exhibition.

那麼在遊戲引擎被更多創作者使用的今天,可能即將誕生出什麼呢?設計師/策展人 John Sharp 在《遊戲之作:論遊戲與藝術的美學》透過大量的案例將遊戲與藝術之間的關係分成四大類:遊戲藝術(Game Art)、藝術遊戲(Artgames)、藝術家的遊戲(Artist’s Games)、遊戲作為媒材(Games as a Medium),這個框架依然適合用來理解當下的創作嗎?抑或邊界其實更加模糊了。

展覽主題「A-Real Engine」一方面指涉電子遊戲如同一部充滿動能的引擎,不斷驅動數位文化的發展。,當代藝術常見的形式,如動力裝置、網路藝術、數位藝術、科技藝術、加密藝術等不同面向的創作,都可以找到與之對應的技術驅動力。當然,電腦遊戲也在其中,甚至演化出如引擎電影(Mmachinima)這樣的創作類型,電腦遊戲相關的軟硬體技術、設計思維、使用者生成的內容都為藝術創作注入活水。另一方面,「A-Real」的否定字首「 A-」標記的是對於真實/不真實、線上/線下、虛擬/現實等區分的明確拒絕,因這樣的區分很可能已經無效且從未適用,遊戲就是一種現實。

遊戲引擎是遊戲開發與運行的環境與規則集(ruleset),展覽則是藝術作品被經驗甚至完成的環境。藝術家們如何透過電腦遊戲的概念與元素,打造新的敘事方式;或如拆開引擎般地解構遊戲機制,帶領觀眾更加理解自身處境,甚至尋找逃出系統控制的路徑,成為一個潛在的破壞者(rule breaker);又或者藉由修復遊戲機台,保存並重現遊戲曾經帶給人們的純粹快樂,既使花口袋硬幣也甘之如飴——這些面向都將在展覽中呈現。

Artist

Theo Triantafyllidis

Jisun KIM

Harold Hejazi / Harriharri

Nao Usami

Larry Achiampong & David Blandy

Xia Han

Team9 & David Yang

Tansy Xiao

Stark PengInvitro media (Xiyue HU, Xing XIAO)

Brent Watanabe

Nanut Thanapornrapee

Chia-Ming LIU, Che-Hsi KUO & Che-Wei HSU

參展藝術家

西奥・特里安塔菲利迪斯

金智善

哈洛・赫加茲(哈里哈里)

宇佐美奈緒

拉里.阿什安普 & 大衛.布蘭迪

夏瀚

Team9 & 楊大毅

肖天時

彭義萍

Invitro media(胡曦月, 肖幸)

布倫特・渡邊

納努特・塔納蓬拉比

劉家銘、郭哲希、許哲維

Chia-Ming LIU, Che-Hsi KUO & Che-Wei HSU, World 1-1 (2023)

Organizer: Department of Cultural Affairs Taipei City Government

Executive Organizer: Digital Art Center, Taipei

Executive Co-Organizer: National Taiwan Education Center

Executive Organizer: Digital Art Center, Taipei

Executive Co-Organizer: National Taiwan Education Center

DAC Team

CEO: Po-Chih HUANG

Executive Director: I-Ching LU

Artistic Director: Hsiang-Wen CHEN

Project Manager: Rachel HUANG

Project Executive: Aya LIU

Technical Coordinator: The Middle of Nowhere

KEey Visual Design: Jr-Shin LUO, Eason FAN

3D Design & Festival Trailer: Jeci CHEN

Design Assistant: Yen-Jui LEE

Executive Assistant: Yu-Hsuan HSIANG

Executive Specialist: Shu-Yin WU, Stella LIOU

Exhibition Specialist: Chen Chen, Beryl HSIEH

Assistants: Chien Yu CHU, Tzu-Ying HO, Jiun-Yi HOU, Nini CHEN, Yen-Ning CHEN, Hou-Zuo CHEN, Pei-Yu CHEN, Yun-Tzu HUANG, Yu-Hsuan TSENG, Chin LIU, Sung-Chun YANG, Allen HSIEH

Executive Director: I-Ching LU

Artistic Director: Hsiang-Wen CHEN

Project Manager: Rachel HUANG

Project Executive: Aya LIU

Technical Coordinator: The Middle of Nowhere

KEey Visual Design: Jr-Shin LUO, Eason FAN

3D Design & Festival Trailer: Jeci CHEN

Design Assistant: Yen-Jui LEE

Executive Assistant: Yu-Hsuan HSIANG

Executive Specialist: Shu-Yin WU, Stella LIOU

Exhibition Specialist: Chen Chen, Beryl HSIEH

Assistants: Chien Yu CHU, Tzu-Ying HO, Jiun-Yi HOU, Nini CHEN, Yen-Ning CHEN, Hou-Zuo CHEN, Pei-Yu CHEN, Yun-Tzu HUANG, Yu-Hsuan TSENG, Chin LIU, Sung-Chun YANG, Allen HSIEH

Photography (Installation view): Anpis Wang

主辦單位:台北市文化局

執行單位:臺北數位藝術中心

協辦單位:國立台灣科學教育館

執行單位:臺北數位藝術中心

協辦單位:國立台灣科學教育館

DAC 執行團隊

執行長:黃博志

行政總監:呂怡青

藝術總監:陳湘汶

數位藝術節專案統籌:黃靖茜

數位藝術節專案執行:劉子誠

數位藝術節技術統籌:無名小鎮工作室

主視覺設計:羅智信、范綱燊

3D設計及形象預告片:陳品蓁

數位藝術節專案設計助理:李延瑞

藝術節專案助理 :向育萱

行政專員:吳書吟、劉家瑜

展覽專員:陳琛、謝博勻

團隊助理:朱千羽、何姿瑩、侯君儀、陳廷妮、陳妍寧、陳厚佐、陳沛羽、黃勻姿、曾郁琁、楊崧均、劉沁、謝艾倫

行政總監:呂怡青

藝術總監:陳湘汶

數位藝術節專案統籌:黃靖茜

數位藝術節專案執行:劉子誠

數位藝術節技術統籌:無名小鎮工作室

主視覺設計:羅智信、范綱燊

3D設計及形象預告片:陳品蓁

數位藝術節專案設計助理:李延瑞

藝術節專案助理 :向育萱

行政專員:吳書吟、劉家瑜

展覽專員:陳琛、謝博勻

團隊助理:朱千羽、何姿瑩、侯君儀、陳廷妮、陳妍寧、陳厚佐、陳沛羽、黃勻姿、曾郁琁、楊崧均、劉沁、謝艾倫

展場靜態記錄:王世邦

Harold Hejazi, Adventures of Harriharri — Trilogy I (2020-2022)